U.S. Elections: Voting Affects Well-Being Among Americans

For Americans, casting a ballot and participating in elections is associated with greater overall community well-being, which includes the ability to live a purposeful and happy life and having the energy and financial freedom to achieve goals based on sound individual resilience and community infrastructure, according to data from the Sharecare Community Well-Being Index (CWBI).

Historically, states with lower unemployment rates and higher levels of educational attainment have coincided with more civic engagement but with the COVID-19 pandemic, record unemployment and civil unrest may prompt more Americans to get to the polls in November.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, job losses across the country reached levels not seen since The Great Depression[1]. Americans with less than a college degree and those who did not graduate from high school have been disproportionately affected[2].

“It is hard to find the silver lining of 2020 amid mounting concerns about financial security, health, and well-being. This health and economic crisis could motivate more people to engage in the upcoming elections, including those who have historically not voted” says Catherine Ettman, a doctoral student at the Brown University School of Public Health and director of strategic development at the Boston University School of Public Health Office of the Dean.

“Since we know that civic engagement contributes to feelings of security and positive outlook, increased voter engagement could also improve community and purpose well-being for those populations, including feeling more aligned to national leadership and more empowered to shape our nation’s future,” Ettman adds.

Voting Tied to Greater Well-Being

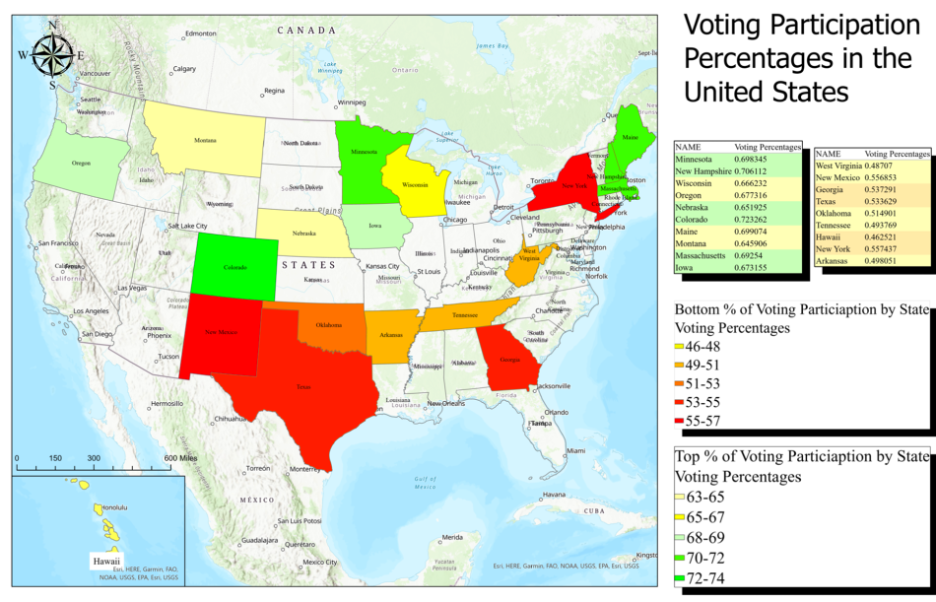

Sharecare’s CWBI, a combined measure that includes individual well-being and social determinants circumstances, found that with the exception of Alaska, which wasn’t included in the analysis, states with the highest levels of voter participation in the 2016 election scored higher, on average, than states with lower levels of voter participation.

For states in the top quintile of voter participation, including states where more than 66% of eligible voters participated in the 2016 presidential election, mean CWBI score was 62.2.

By comparison, states in the lowest quintile of voter participation, including states where fewer than 52% of eligible voters participated in the 2016 election, mean CWBI scores dropped to 55.2, a 7+ point differential in CWBI score compared to states in the top quintile of voter participation.

Barriers to Voting May Affect Well-Being

In addition to higher on average CWBI scores, states in the top quintile for voter participation saw above average scores across all 10 CWBI domains, and more than 1 point above average scores across 4 of 10 CWBI domains, including healthcare access, financial well-being, economic security, and housing and transportation (reference Table 1).

The largest differential observed was in the housing and transportation domain, including 23% above average levels of public transit use, suggesting that enhanced infrastructure better enables individuals, particular those with lower socioeconomic status, to exercise their right to vote.

| CWBI Domain | Mean Score – Top Quintile States by Voting Participation | Mean Score – All States | Difference |

| Financial Well-Being | 61.88 | 60.22 | 1.66 |

| Social Well-Being | 57.59 | 57.14 | 0.45 |

| Purpose Well-Being | 58.95 | 58.84 | 0.11 |

| Physical Well-Being | 61.16 | 60.20 | 0.96 |

| Community Well-Being | 61.30 | 60.72 | 0.59 |

| Economic Security | 55.74 | 53.13 | 2.61 |

| Housing & Transportation | 59.01 | 55.69 | 3.32 |

| Healthcare Access | 60.26 | 58.92 | 1.34 |

| Food Access | 58.90 | 58.35 | 0.55 |

| Resource Access | 47.54 | 47.48 | 0.06 |

On the opposite end of the spectrum, states in the bottom quintile for voting participation had below average scores across all 10 CWBI domains, and more than 1 point below average scores across financial well-being, food access, and economic security (reference Table 2).

The largest differential in the bottom quintile was identified in the economic security domain, including 6% lower rates of employment for individuals aged 16 to 54, and 21% higher rates of individuals living with household incomes below the poverty line.

| CWBI Domain | Mean Score – Bottom Quintile States by Voting Participation | Mean Score – All States | Difference |

| Financial Well-Being | 59.14 | 60.22 | -1.08 |

| Social Well-Being | 56.90 | 57.14 | -0.25 |

| Purpose Well-Being | 58.69 | 58.84 | -0.15 |

| Physical Well-Being | 59.24 | 60.20 | -0.96 |

| Community Well-Being | 60.29 | 60.72 | -0.43 |

| Economic Security | 49.54 | 53.13 | -3.59 |

| Housing & Transportation | 54.93 | 55.69 | -0.76 |

| Healthcare Access | 58.27 | 58.92 | -0.64 |

| Food Access | 56.01 | 58.35 | -2.33 |

| Resource Access | 47.00 | 47.48 | -0.48 |

Employment rates for individuals with less than a high school degree plummeted from 7.2% in February 2020 to more than 18% in May 2020[3], Pew Research Center reports, noting that this disparitiy could motivate more people with less education to get to the polls.

Economic adversity, however, does not always lend to higher voter turnout for those most affected. Research from the American Journal of Political Science asserts that “economic problems both increase the opportunity costs of political participation and reduce a person’s capacity to attend to politics[4],” suggesting that significant hardships may serve as a barrier to civic engagement.

Younger Voters Gaining Political Power

Of the top quintile states for voter participation, 50% also ranked in the top quintile for employment rates for individuals aged 16 to 54. Moreover, Minnesota, considered a key swing state in 2020, ranks highest in both employment for individuals aged 16 to 54 and voter participation in the 2016 election, the CWBI revealed.

Currently, more than half of Americans are millennials or younger, according to the the Brookings Institution. After analyzing Census Bureau data compiled in July 2020, these younger individuals comprise 50.7% of the nation’s population, outnumbering the 162 million Americans classified as members of the Gen X, baby boomer or older generations.

More importantly, millennials and some members of Gen Z now account for 37% of eligible voters—roughly the same share of voters as Baby Boomer and older populations, Brookings reported.

If voter turnout during the 2018 midterm elections is any indication of what is to come in November 2020, a Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data found that Generation Z, Millennial and Generation X voters accounted for a narrow majority of those who showed up at the polls.

A 2018 pre-election survey conducted by Tufts Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement also found that activism among younger voters is on the rise. The survey showed the percentage of these adults who had engaged in a protest tripled between 2016 and 2018. The researchers noted that social media, which has become a ubiquitous part of daily life, may have an important role to play in youth activism, noting that members of Gen Z and millennials who are interested in elections may use these platforms to become more involved and connect with political organizations and candidates.

Supporting Civic Engagement to Improve Well-Being

Participation in civic life is one important way for Americans to improve their sense of purpose, connectedness and social well-being, according to the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) also contends that through voting and other forms of civic engagement, “people develop and use knowledge, skills and voice to cultivate positive change. Such actions can help improve the conditions that influence health and well-being for all.”

“At this point, what we can do is create the means for all individuals to vote, including ensuring broad access to voting by mail through USPS funding and increased volunteerism to get individuals to the polls safely on election day,” says Ettman.

“Based on data from sources like the World Happiness report and the Sharecare Community Well-Being Index,” Ettman adds, “we know that states and countries with higher levels of voter participation exhibit broadly enhanced levels of happiness, outlook, and fiscal stability. This means that regardless of political affiliation, we should all be in support of increasing voter participation, locally and nationally, and pay attention to social determinant contexts critical to enabling voter participation across all geographies and demographics.”

Some 40 percent of Americans who were eligible to vote failed to do so in the 2016 presidential elections, according to the United States Election Project[5].

An August 2020 survey conducted by Pew Research Center found, however, that more voters believe it “really matters” who wins the 2020 Presidential election than any other bid for the oval office in the past two decades.

The November 3, 2020 presidential election will take place in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Election officials around the country are gearing up for a surge of mail-in and absentee ballots because of coronavirus safety concerns. In-person voting will also take place as usual, which could lead to long lines and crowded polling sites.

As a result, casting a ballot in the 2020 election requires more preparation and safety precautions than in previous years.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a guide for polling stations and voters, explaining how to follow the best health and safety practices.

All U.S. citizens age 18-years and older cannot be denied the right to vote, regardless of race, religion, sex, disability, or sexual orientation. In every state except North Dakota, however, citizens must register to vote. State laws regarding the registration process vary across the country.

State by state information about registering to vote, voting by mail, polling place locations and how to volunteer as a poll worker can be found here.

“Voting is a good proxy for civic engagement and investment in one’s community. Caring about the community around us, and being engaged in the democratic process, can help personal health and improve community well-being,” Ettman says.

[1] https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/05/us-job-losses-due-covid-19-highest-great-depression

[2] https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/evidence-base/individuals-with-low-incomes-less-education-report-higher-perceived-financial-health-threats-from-covid-19/

[3] https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/11/unemployment-rose-higher-in-three-months-of-covid-19-than-it-did-in-two-years-of-the-great-recession/

[4] https://www.jstor.org/stable/2110837

[5] http://www.electproject.org/2016g