Student Debt Linked to Worse Health and Less Wealth

Although graduates with no student loan debt are slightly more likely than their indebted peers to be thriving socially, the differences are not statistically significant.

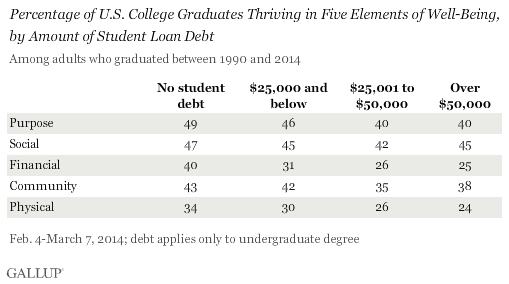

Gallup finds the starkest differences among these groups in the areas of financial and physical well-being. Higher debt signifies lower likelihood of thriving in these two areas of well-being. Graduates who went the deepest into debt to obtain their college degree, for instance, are far less likely to be thriving than graduates who took out no debt, by 15 percentage points in financial well-being and 10 points in physical well-being. The pattern is similar for graduates’ sense of purpose, although those who borrowed over $50,000 are just as likely to be thriving in this element as those who borrowed $25,001 to $50,000. The relationship is less straightforward for graduates’ community well-being, though again, graduates who took on the most debt for their degree are less likely to be thriving in this element than those who did not take out any loans for their undergraduate education.

These results are based on the inaugural Gallup-Purdue Index, a joint-research effort with Purdue University and Lumina Foundation to study the relationship between the college experience and college graduates’ lives. The Gallup-Purdue Index is a comprehensive, nationally representative study of U.S. college graduates with Internet access. According to a 2013 Census Bureau report, 90% of college graduates in the U.S. have access to the Internet. This analysis is based on a Web study conducted Feb. 4-March 7, 2014, with more than 11,000 adults who graduated college between 1990 and 2014.

Using the Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index, the Gallup-Purdue Index measures key outcomes to determine whether college graduates have good lives. The Well-Being Index is organized into five elements of well-being:

- Purpose: liking what you do each day and being motivated to achieve your goals

- Social: having supportive relationships and love in your life

- Financial: managing your economic life to reduce stress and increase security

- Community: liking where you live, feeling safe, and having pride in your community

- Physical: having good health and enough energy to get things done daily

Gallup classifies those who respond, at the element level, as “thriving” (well-being that is strong and consistent), “struggling” (well-being that is moderate or inconsistent), or “suffering” (well-being that is low and inconsistent).

The student loan debt figures this analysis uses are reported by the respondents and are adjusted for inflation to today’s dollars. Figures only apply to undergraduate student loan debt. Gallup did not ask respondents about the status of their student debt or inquire into how much of their loan they have repaid.

As college costs rise and enrollment increases, the amount of outstanding undergraduate student debt in the U.S. continues to climb. The amount of student debt now stands at over $1 trillion for both undergraduate and graduate loans and exceeds Americans’ overall credit card debt, according to the Federal Reserve. In particular, estimates put the average amount of undergraduate student loan debt for the class of 2014 at just over $33,000, a substantial increase from $18,600 in 2004.

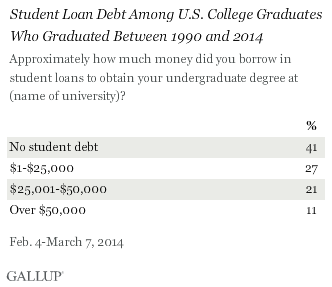

Most degree earners in Gallup’s survey graduated with debt: 59% of those graduating between 1990 and 2014 had borrowed at least some amount for educational expenses, including 21% who borrowed between $25,001 and $50,000 and 11% who borrowed over $50,000. The remaining 27% borrowed less than $25,000.

As the amount of money students are borrowing continues to grow, the importance of student debt as a U.S. political issue has increased. Politicians and higher education leaders express concern that highly indebted graduates are unable to forge an economic identity after graduation, putting off major purchases and suffering from low savings. Congress, for instance, has debated proposals that could bring down the cost of monthly student debt payments for borrowers. The U.S. Treasury, for its part, is also exploring ways to help make debt repayments more affordable for some student borrowers.

The findings from the Gallup-Purdue Index raise another important concern about student debt: its link to lower well-being. However, the findings do not necessarily demonstrate that higher amounts of student loan debt causes lower well-being among graduates. Other factors that often determine whether students take out loans for college and how much they borrow — the family’s household income, socio-economic status, the type of school attended, the chosen field of study, and the student’s ability to get scholarships and financial aid — may be the same factors that influence graduates’ future well-being.

While many — including Secretary of Education Arne Duncan — refer to a college degree as “the great equalizer” that puts workers on a level playing field, some studies show that the salutary economic effects of a college degree can be mitigated by other factors, such as a person’s background. But it is worth noting that even after controlling for the highest level of education obtained by the respondent’s mother, a common proxy for socio-economic status, the relationship between higher undergraduate student loan debt and lower well-being holds true.

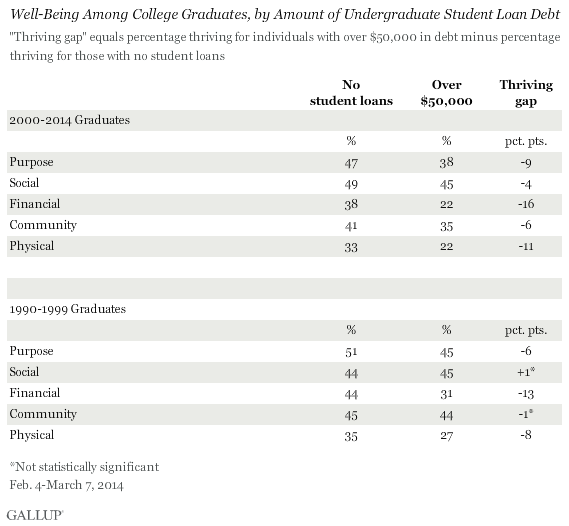

Link Between Student Debt and Lower Well-Being Holds Across Graduation Classes

This study’s large sample includes U.S. adults who graduated college over a 25-year time span, allowing Gallup to see how the interaction of well-being and student debt holds over time. Given standard repayment plans, graduates earning their degrees in the 1990s might consider their student loans a distant memory, as opposed to more recent graduates who are still chipping away at their educational debt. Nonetheless, Gallup’s analysis shows that important well-being differences still exist between the heaviest borrowers and those with no loan debt, and this applies to 1990s graduates as well as the more recent 2000-2014 cohort.

Relatively recent college graduates — those who earned their degree from 2000 to 2014 — who have more than $50,000 in student debt are significantly less likely to be thriving financially and physically than their counterparts without loans. They are also less likely to have a strong sense of purpose and to be thriving in their community well-being. Notably, for 2000-2014 graduates, the most indebted degree holders are less likely to be thriving in social well-being, something that is not true of the larger sample.

But older graduates who took out large student loans also differ from their fellow graduates in their current well-being. Though their student debt is likely paid off, those who graduated in the 1990s and borrowed more than $50,000 have lower financial, physical, and purpose well-being compared with those who never took out loans.

In financial well-being, older graduates that had large student loans trail behind their debt-free peers by 13 points in terms of thriving rates, nearly as large as the gap among the two of graduate types for the 2000-2014 cohort.

Large “thriving gaps,” — the difference between the percentage of graduates with $50,000 or more in student loans thriving in one element from the percentage of debt-free graduates thriving in that element — exist for physical well-being (-8 points) and purpose well-being (-6 points). In both instances, these differences are comparable to discrepancies observed in the younger group of graduates. On the other hand, unlike the younger group of college graduates, graduates of the 1990-1999 era have little differences in thriving in the elements of community and social well-being, regardless of how much they borrowed to get their degree.

There are many possible reasons why those who took out student loans more than 20 years ago still have lower financial, physical, and purpose well-being today. The possession and repayment of debt is known to have negative ripple effects that might not disappear once the financial obligation does. It may be, for example, that the years spent paying down debt rather than securing savings leads to financial insecurity, or that the physical health problems that are often associated with debt persist.

Implications

President Barack Obama recently commented on the challenge of paying for college, saying, “At a time when higher education has never been more important, it’s also never been more expensive. Over the last three decades, the average tuition at a public university has more than tripled.” But, as Obama conceded in the same speech, college is a “smart investment.” The wisdom of this investment is often framed in terms of the economic benefits a degree can bring, rather than on a broader set of criteria, such as if a college degree — and its associated costs — leads to a rewarding, healthy life in the long run.

Recent research suggests that most college graduates will eventually pay down their debt, partly because of the increased earning power commanded by those degrees. And, indicating that the loan process may be working, the vast majority of student loan accounts are not in delinquency — though the rate is rising. But findings from the Gallup-Purdue Index show that there may be costs associated with considerable levels of undergraduate debt that go beyond repayment. Student debt is linked to lower financial, purpose, physical, and community well-being. Notably, well-being is worse for students taking out more than $50,000 worth of student debt, suggesting student debt is most problematic when it is substantial. This pattern is consistent across two decades of graduates, meaning it includes many individuals who have paid off their debt entirely.

Although the analysis clearly shows a link between student debt and well-being that continues later if life, the mechanisms driving that relationship are unclear and cannot be established by this study. Specifically, it is unclear if the debt itself and its effect on future life events drags down a person’s well-being, of if the conditions that lead one to borrow for college, such as family income, are related to well-being and have effects that persist later in life.

Studies show that high student debt can result in the deferral of major life events, such as marriage and homeownership. High student debt can also result in a graduate pursuing a career path he or she would not have taken otherwise. These new insights from the Gallup-Purdue Index suggest the legacy of high student debt may be lower well-being that lasts for many years after graduates receive their diploma.

More broadly, there are many factors to consider when measuring the outcomes of a college education — not just salaries or employment rates. The Gallup-Purdue Index provides the most comprehensive examination of the relationship between the college experience and whether college graduates have great jobs and great lives.

SURVEY METHODS

Results for the Gallup-Purdue Index are based on Web surveys conducted Feb. 4-March 7, 2014, with a random sample of 29,560 respondents with a bachelor’s degree or higher, aged 18 and older, with Internet access, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

For results based on the total sample of 1990-2014 college graduates, the margin of sampling error is ±1.4 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.

The Gallup-Purdue Index sample was compiled from two sources: the Gallup Panel and the Gallup Daily tracking survey.

The Gallup Panel is a proprietary, probability-based longitudinal panel of U.S. adults who are selected using random-digit-dial (RDD) and address-based sampling methods. The Gallup Panel is not an opt-in panel. The Gallup Panel includes 60,000 individuals who Gallup surveys via phone, mail, or Web. Gallup Panel members with a college degree and access to the Internet were invited to take the Gallup-Purdue Index survey online.

The Gallup Daily tracking survey sample includes national adults with a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by time zone within region. Landline and cellular telephone numbers are selected using RDD methods. Landline respondents are chosen at random within each household based on which member had the most recent birthday. Gallup Daily tracking respondents with a college degree who agreed to future recontact were invited to take the Gallup-Purdue Index survey online.

Gallup-Purdue Index interviews are conducted via the Web in English only. Samples are weighted to correct for unequal selection probability and nonresponse. The data are weighted to match national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, and region. Demographic weighting targets are based on the most recent Current Population Survey figures for the aged 18 and older U.S. bachelor’s degree or higher population.

All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting.

In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

For more details on Gallup’s polling methodology, visit www.gallup.com.