Though Insured, Many U.S. Asians Lack a Personal Doctor

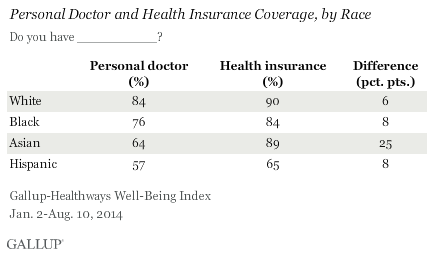

WASHINGTON, D.C. — In the U.S., Hispanic and Asian adults are significantly less likely than white and black adults to report having a personal doctor. While Hispanics’ lower rates of having health insurance can partially explain their lower rates of having a personal doctor, Asians are among the groups most likely to have health insurance.

Further illustrating the varying degree to which having health insurance is related to having a personal doctor for Asians and Hispanics, Gallup finds that more than three-quarters of Asians (78%) who lack a personal doctor are insured vs. 35% of Hispanics who lack a personal doctor. This pattern has been consistent since Gallup and Sharecare began tracking these measures in 2008.

These data, collected as part of the Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index, are based on respondents’ self-reports of personal doctor and health insurance status based on the questions, “Do you have a personal doctor?” and, “Do you have health insurance coverage?”

One possible reason why Asians, despite being among the groups most likely to be insured, are less likely to have a personal doctor is because they are, on average, healthier. Previous Gallup research has found that Asians are the least likely racial and ethnic group to say they have been diagnosed with chronic health conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, depression, asthma, diabetes, cancer, and heart attack. However, it is also possible that Asians are less likely to say they have been diagnosed with these conditions because they lack a personal doctor who would make such a diagnosis in the first place. Independent of conditions that may be diagnosed by a doctor, Asians are also less likely than other racial and ethnic groups to be obese and to smoke.

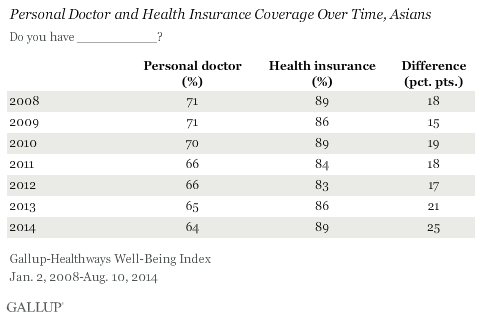

The gap between the percentage of Asians who have health insurance and the percentage who have a personal doctor has been much higher than among other racial and ethnic groups in every year since 2008. Asians’ self-reports of having a personal doctor has gradually decreased over the past seven years, even as their rate of having health insurance has remained steady or increased. The gap between Asians who have health insurance and Asians who have a personal doctor has increased significantly in 2014 to date, to 25 percentage points.

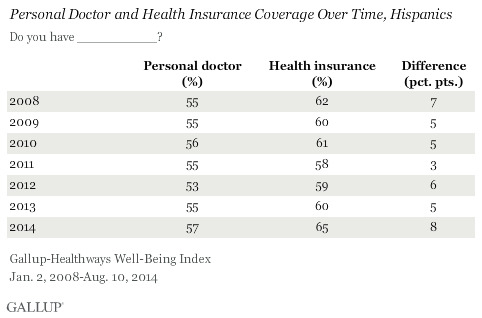

On the other hand, Hispanics’ self-reports of having a personal doctor and having health insurance have generally increased since 2012. Over the same time period, the gap between Hispanics with health insurance and Hispanics with a personal doctor increased, indicating that they are purchasing health insurance at faster rate than they are finding a personal doctor.

Both Asian and Hispanic Americans may have cultural and logistical barriers that decrease their likelihood of having a personal doctor. Both cultures have a long history of preferring non-Western medicine, which may lead to reluctance in accepting American healthcare and selecting a personal doctor. Asians, particularly those from China, believe in traditional Chinese medicine, which relies more heavily on acupuncture and herbal remedies. Similarly, Hispanics often utilize herb-based treatments to treat common ailments.

Logistical barriers may also exist, such as language. Particularly for the older generations, learning English medical terms and communicating with a doctor or health insurance company can prove challenging. Culture shock and unfamiliar reservation systems might also reduce their likelihood of seeking out personal doctors.

Finally, it is possible that Asians may actually see doctors often, but instead of having a “personal doctor” as asked in the question, they use storefront clinics, emergency rooms, or other ways of accessing health care on an ad hoc basis.

Older, High-Income, Married Are Most Likely to Have Personal Doctor

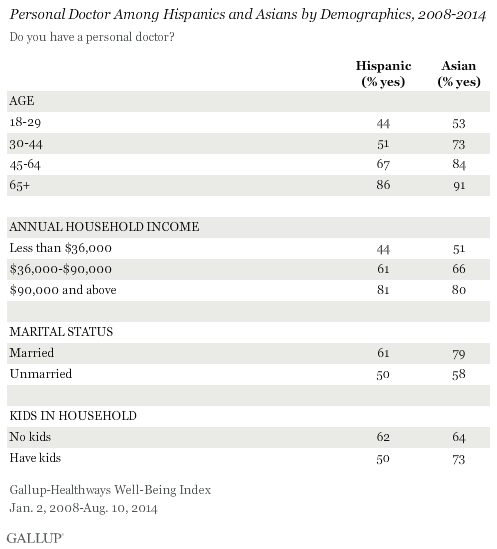

Older Asians and Hispanics are more likely to have a personal doctor than are those who are younger. Among those who are 65 years and older, 86% of Hispanics and 91% of Asians have a personal doctor. Further, the percentage who have a personal doctor increases steadily with age for both groups.

As income levels increase, both Asian and Hispanic adults become more likely to have a personal doctor. Within the highest income group, about 80% of both Asians and Hispanics say that they have a personal doctor. The likelihood of having a personal doctor also increases among those who are married in both groups — 61% of married Hispanics report having a personal doctor, and 79% of Asians who are married do the same.

Hispanics with children in their household are less likely to have personal doctor (50%) than those who do not have kids at home (62%). Conversely, Asians with children in the home are more likely to have a personal doctor than those who do not, 73% vs. 64%, respectively.

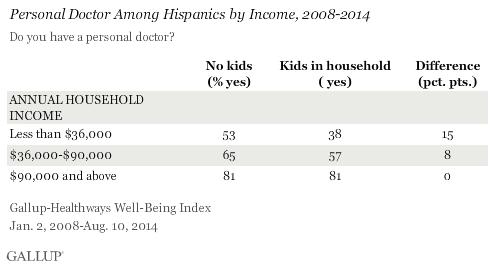

Income Boosts the Likelihood of Having Personal Doctors for Hispanics With Kids at Home

For Hispanics with children in the household, income may be the determining factor behind the lower percentage who have a personal doctor compared with those who do not have children in the home. Within the lowest income group, those who do not have kids are 15 percentage points more likely to have a personal doctor. Most likely those with children in the home are spending their income on items necessary for child rearing. Among the highest income group, however, there is no difference in the percentage who report having a personal doctor between those who do and do not have children at home.

Implications

One of the main objectives of the Affordable Care Act is to increase the percentage of the population with health insurance, which in turn could be expected to increase access to healthcare. The increasing gap between the percentage who are insured and those who have a personal doctor for both Asians and Hispanics suggests that factors other than health insurance — including income, having children, and cultural and logistical barriers — may play a role in increasing access to care.

Understanding the factors that decrease the likelihood of having a personal doctor, beyond insurance and income, for Asians and Hispanics is important. Gallup research shows that the majority of Americans with personal doctors have conversations with them about preventative care and healthy behaviors, including exercise, eating healthy, and not smoking. This is particularly important among those with lower incomes, as those in poverty are more likely to suffer from chronic disease.

Removing known barriers to having a personal doctor may help increase access to care. One potential approach is to provide current U.S. personal doctors with more resources and connections to various Asian and Hispanic treatments, like Chinese acupuncture clinics, for example, and for insurance companies to cover such services.

To decrease logistical barriers to finding a personal doctor, medical communities, insurers, and local governments might partner to create online healthcare communities that offer advice to Asians and Hispanics. This type of community might also increase familiarity with the healthcare system and support doctor-patient relationships. To overcome language barriers, communities and medical associations could consider recruiting Chinese or Spanish translators as volunteers to help non-English speakers communicate with their personal doctors. Further, areas with larger Hispanic or Asian populations could seek to hire doctors who are bilingual.

Finally, governments and communities could also partner with medical care facilities to create solutions specifically aimed at ensuring that low-income families, particularly Hispanics with children, are able to find personal doctors. Information about programs could be posted in both Spanish and English within communities.

SURVEY METHODS

Results are based on telephone interviews conducted as part of the Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index survey Jan. 2, 2014-Aug. 10, 2014, with a random sample of 108,440 adults, including 9,669 and 2,299 self-identified Hispanics and Asians respectively, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

For results based on the total sample of national adults, the margin of sampling error is ±0.09 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.

Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones, with interviews conducted in Spanish for respondents who are primarily Spanish-speaking. Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by time zone within region. Landline and cellular telephone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods. Landline respondents are chosen at random within each household on the basis of which member had the most recent birthday.

Samples are weighted to correct for unequal selection probability, nonresponse, and double coverage of landline and cell users in the two sampling frames. They are also weighted to match the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, region, population density, and phone status (cellphone only/landline only/both, and cellphone mostly). Demographic weighting targets are based on the most recent Current Population Survey figures for the aged 18 and older U.S. population. Phone status targets are based on the most recent National Health Interview Survey. Population density targets are based on the most recent U.S. census. All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting.

In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

For more details on Gallup’s polling methodology, visit www.gallup.com.