COVID-19 Worsening Food Access Inequalities in the United States

There are few people around the world who have not felt the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Here in the United States, the highly contagious coronavirus has upended the lives of millions of Americans.

Certain parts of the country may be more accustomed to being in the path of natural disasters, such as residents of “Tornado Alley” or those living along the Gulf Coast who are typically forced to brace for a string of hurricanes around this time each year.

But with roughly 6 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and nearly 200,000 lives lost in the United States alone as of late August 2020, it’s clear that this global health crisis has affected Americans living in every state—regardless of age, race, ethnicity, income level or gender. Recent data from Sharecare’s Community Well-Being Index (CWBI), however, suggests that some regions and more vulnerable populations are bearing a disproportionate burden of the disease and it’s effects than others.

Sharecare’s CWBI sheds light on Americans’ social determinants of health (SDOH)—the properties of the places in which they work and live, their access to healthy food, green spaces, quality education, healthcare or safe and affordable housing as well as their financial security. Understanding these factors, which play a significant role in people’s physical health and overall well-being, can help explain why certain pockets of the United States may be struggling more than others, particularly amid the pandemic.

One social determinant of health, in particular, that has shifted greatly in recent months: food security.

“A benefit of SDOH data, which includes measures of food access and economic security at the community scale, is that it can aid local and state governments plan where to focus efforts to ensure that the most vulnerable maintain access to nutrition,” says Kevin Lane, PhD, MA, assistant professor of environmental health at Boston University.

Greater Food Insecurity Amid COVID-19

Before the pandemic, households with children younger than 18 had a food insecurity rate of 15 percent, according to the Brookings Institution. The nonprofit public policy organization reports that this has surged to 34.5 percent as of April 2020. [1] The hunger-relief organization, Feeding America, also reports that the number of people in the United States who are food insecure has surged to 54 million—up from a pre-pandemic level of 37 million.[2]

COVID-19 has led to rapid changes in the retail food industry, which could exacerbate existing food access inequalities.[3]

“In total between March and June 2020, eating and drinking place sales levels were down more than $116 billion from expected levels, based on the unadjusted data,” Bruce Grindy, chief economist of the National Restaurant Association, stated in a July 2020 news release. “The total shortfall in restaurant and food service sales reached an estimated $145 billion during the first four months of the pandemic.”

A recent report of listed business within Yelp revealed that more than 26,000 restaurants have closed across the United States[4]. Additionally, business repositories such as Reference USA[5] have identified verified food retail closures of 7% to 23% by industry categories with large spatial variations between and across states.

North American Industry classification System (NAICS) codes that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Department of Agriculture use to identify businesses in order to calculate food deserts and swamps, respectively, are listed in the table below. The short and long-term effects of such a rapid change in retail food access could have potential health implications.

Percent of closed food retail businesses in 2020 by type of food retail based on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes. Data for table was obtained from Reference USA on 8/16/2020.

| Food Retail (NAICS code) | United States |

| Total Restaurants (72251117) | 13.3% |

| Limited-Service Restaurants (722513) | 16.7% |

| Supermarkets and Large Grocery Stores ≥ 50 employees (445110) | 14.5% |

| Small Grocery Stores ≤ 4 employees (445110) | 12.2% |

| Fruit and Vegetable Markets (445230) | 10.2% |

| Warehouse Clubs (45231101) | 15.8% |

| Convenience Stores (445120) | 8.0% |

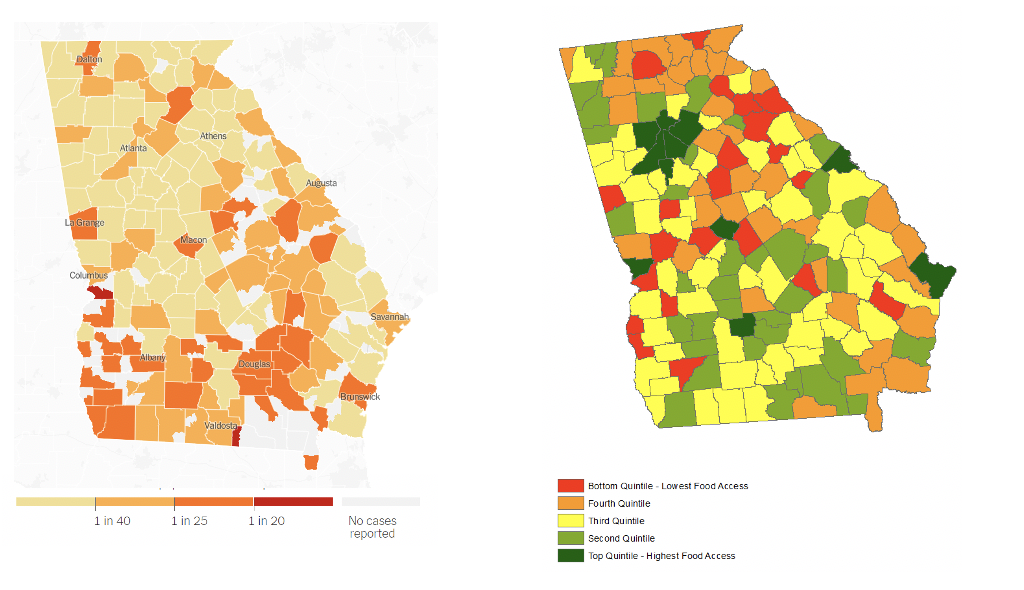

For example, the maps below show that in southern Georgia, per capita cases of COVID-19 overlap with the areas that have lower scores on Sharecare’s Community Well-Being Index Food Access domain score. Meanwhile, Columbus, Georgia has one of the highest per capita rates of COVID-19 infections in the state and is also one of the lowest-rated areas for food access.

If retail and food industry closures are happening in communities, which already face food access issues, this could lead to considerable vulnerability in those populations.

“There’s a major concern about the ability to obtain proper nutrition among vulnerable populations, such as young children. Access to nutrtion is vital during early childhood and could affect future health across lifetimes,” says Lane. “Decreased access to food due to retail food stores closing coupled with increased unemployment make federal nutrition assistance programs even more important.”

The National School Lunch Program and the Child and Adult Care Food Program help improve physical access to food, while the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) support the ability to purchase food from retail outlets, Lane explains. “These programs are essential mechanisms to address food insecurity for our most vunerable populations and make sure there is equitable access to obtain nutrition,” he adds.

Quantifying the Effects of COVID-19

Food access is just one of the many social determinant of health measures that may play a role in people’s health and well-being and can be used to quantify the impact of COVID-19 on a community.

Food insecurity is closely tied to unemployment and homelessness due to lost income, according to a recent commentary published in the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. The researchers noted that minorities are facing higher rates of job losses than other groups.

As of August 27—more than five months after the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic—27 million people are receiving some form of unemployment insurance, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.[6]

The intersection of these factors in specific communities could dramatically worsen the financial and health issues brought on by the pandemic. Conversely, improvements in social determinants of health could also have a protective effect.

How these elements intersect with one another, and how COVID-19 has affected communities across the country can be explored in greater detail in Sharecare’s 2019 Community Well-Being Rankings report.

[1] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/05/06/the-covid-19-crisis-has-already-left-too-many-children-hungry-in-america/

[2] https://www.feedingamericaaction.org/the-impact-of-coronavirus-on-food-insecurity/

[3] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-and-covid-19

[4] https://abcnews.go.com/Business/16000-restaurants-closed-permanently-due-pandemic-yelp-data/story?id=71943970

[5] Infogroup, Inc. (2020). Hershey Company. Retrieved August 16th, 2020, from ReferenceUSA database.