Young Black Males’ Well-Being Harmed More by Unemployment

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Unemployment negatively affects well-being more for young black males

- Attachment to community plummets when out of a job

- Reports of safety and security worsen sharply when unemployed

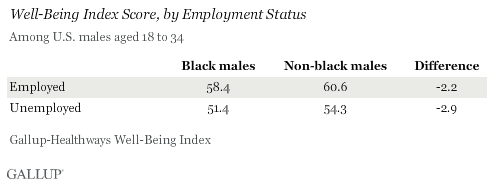

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Among U.S. men, the gap in well-being experienced by blacks under the age of 35 compared with their non-black counterparts grows still wider when unemployed, according to the Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index. Compared with the 2.2-point gap in Well-Being Index scores measured among those who are employed, the 2.9-point gap between young black and non-black unemployed men is significantly larger.

These findings build on an earlier report showing more broadly that young black males in the U.S. have lower well-being than young non-black males, and this difference is wider than what is found among those between the ages of 35 and 64. Young black males as a group also have higher unemployment, lower graduation rates, less access to healthcare and higher incarceration rates than other racial, age and gender groups in the U.S. And in 2014, the particular difficulties this group has in dealings with law enforcement became headline news resulting from events in Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York, involving the deaths of young black men at the hands of police. This article continues to explore the well-being of young black males in comparison with other groups, focusing here on employment status.

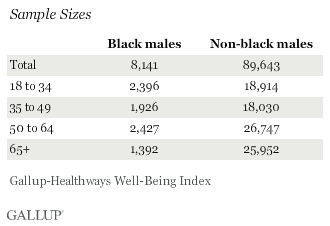

These results are based on over 33,000 interviews with American men aged 18 to 34, from Jan. 2 to Dec. 30, 2014, conducted as part of the Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index. This includes 458 interviews with unemployed black males aged 18 to 34 and another 3,030 interviews with employed black males aged 18 to 34.

Community Well-Being Sinks for Unemployed Young Black Males

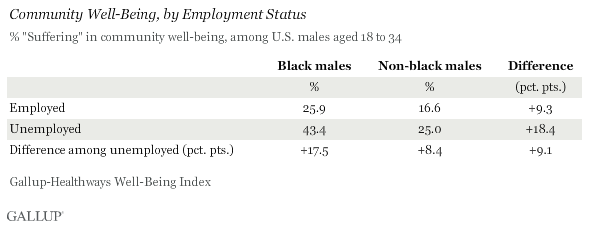

Beyond the composite Well-Being Index score, Gallup sees a particularly wide gap in the “community” component of well-being among unemployed young black men.

As one of the five elements of well-being, Gallup and Sharecare define community well-being through several individual metrics, including those that measure liking where you live, feeling safe and having pride in your community. Respondents are categorized as thriving, struggling or suffering based on their respective levels of well-being.

While the percentage of people categorized as suffering on the community well-being dimension jumps for all adults when unemployed, the increase is particularly great among young black males, increasing from an already elevated 25.9% when employed to 43.4% when unemployed. Among non-black males aged 18 to 34, the percentage who are suffering also increases with unemployment, but more modestly than is seen among blacks, from 16.6% to 25.0%.

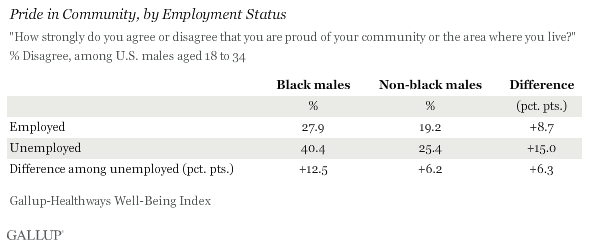

The individual metrics that compose community well-being all show similar widening of the well-being gap between black males and non-black males once employment status is a factor. For example, young black males who say they are not proud of the community in which they live climbs from 27.9% among those who are employed to 40.4% when unemployed. Non-blacks also report elevated levels of disagreement, but at a substantially reduced rate.

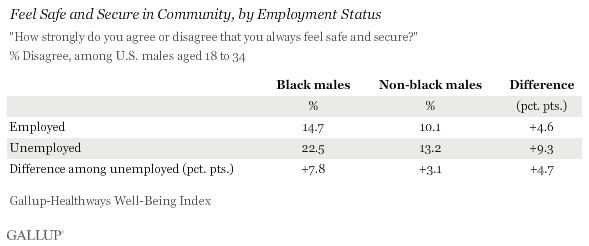

Reports of safety and security among young adult males also suffer when those individuals are unemployed, and even more so among blacks. The percentage of blacks aged 18 to 34 who report not feeling safe or secure goes from 14.7% when employed to 22.5% when unemployed, an increase that more than doubles what is reported by non-blacks.

Implications

The relationship between unemployment and well-being — regardless of race, gender or age — is negative and almost certainly reciprocal. When involuntarily outside of the workforce, adults are more likely to be obese; report more daily physical pain, stress and worry; and experience depression. These conditions simultaneously may be a barrier to finding work, while at the same time may be caused or exacerbated by extended unemployment.

But the link between being unemployed and having lower well-being is not always the same across racial divides. The absence of a job affects the well-being of young black males distinctly more so than their non-black counterparts in some key areas of community well-being, underscoring the acute challenges for city leaders. This is exacerbated by official Bureau of Labor Statistics unemployment rates of 12.4% among black men, more than double the 5.1% reported among men in general.

Having a job means having more money to spend, generally affording residents of a community safer living conditions, more opportunities to experience and learn new things, and greater avenues for direct participation in their community. These can have the effect of enhancing pride in the community and satisfaction with it. The absence of a job, in turn, generally leads to less desirable living conditions, more time spent in less safe conditions and a suppressed sense of pride in the area where one lives. In urban areas, where young black males are demographically more likely to reside, the absence of a job exacerbates these differences.

With Americans’ satisfaction with the state of race relations sharply down since 2008 and the U.S. Department of Justice report on Ferguson’s police department making headlines, the role of good, available jobs may sometimes be understated as a means to enhancing the attachment to community for all residents in any given city, but especially for young black males in particular. John Hope Bryant, CEO of Operation Hope and a noted thought leader focused on the challenges facing black men in American society today, notes, “Young black men are feature actors in a suffering index, because of a lost sense of hope in their lives. The most dangerous person in the world is a person with no hope. We have traditional learning models, and now problem-based learning models. What we need now are aspirational-based learning models. Things that connect education with life aspirations.”

SURVEY METHODS

Results are based on telephone interviews conducted as part of the Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index survey Jan. 2-Dec. 30, 2014, yielding a random sample of 33,549 adult men, aged 18 to 34, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, selected using random-digit-dial sampling. Among these interviews, 3,030 were with employed blacks and 458 were with unemployed blacks seeking to gain employment.

For results based on the sample sizes noted above, unemployed black respondents have a maximum expected error range of about ±3.8 percentage points (for suffering, pride in community and safety) and ±1.6 index points (Well-Being Index) at the 95% confidence level. Among employed black respondents, these margins of error reduce to ±1.6 percentage points and ±0.6 index points. Corresponding margins of error for non-black groups are much smaller.

Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones, with interviews conducted in Spanish for respondents who are primarily Spanish-speaking. Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by time zone within region. Landline and cellular telephone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods. Landline respondents are chosen at random within each household on the basis of which member had the most recent birthday.

Samples are weighted to correct for unequal selection probability, nonresponse and double coverage of landline and cell users in the two sampling frames. They are also weighted to match the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, region, population density, and phone status (cellphone only/landline only/both, and cellphone mostly). Demographic weighting targets are based on the most recent Current Population Survey figures for the aged 18 and older U.S. population. Phone status targets are based on the most recent National Health Interview Survey. Population density targets are based on the most recent U.S. census. All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting.

In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

For more details on Gallup’s polling methodology, visit www.gallup.com.